by Atifa Annabi (ORCiD: 0009-0005-1838-9389)

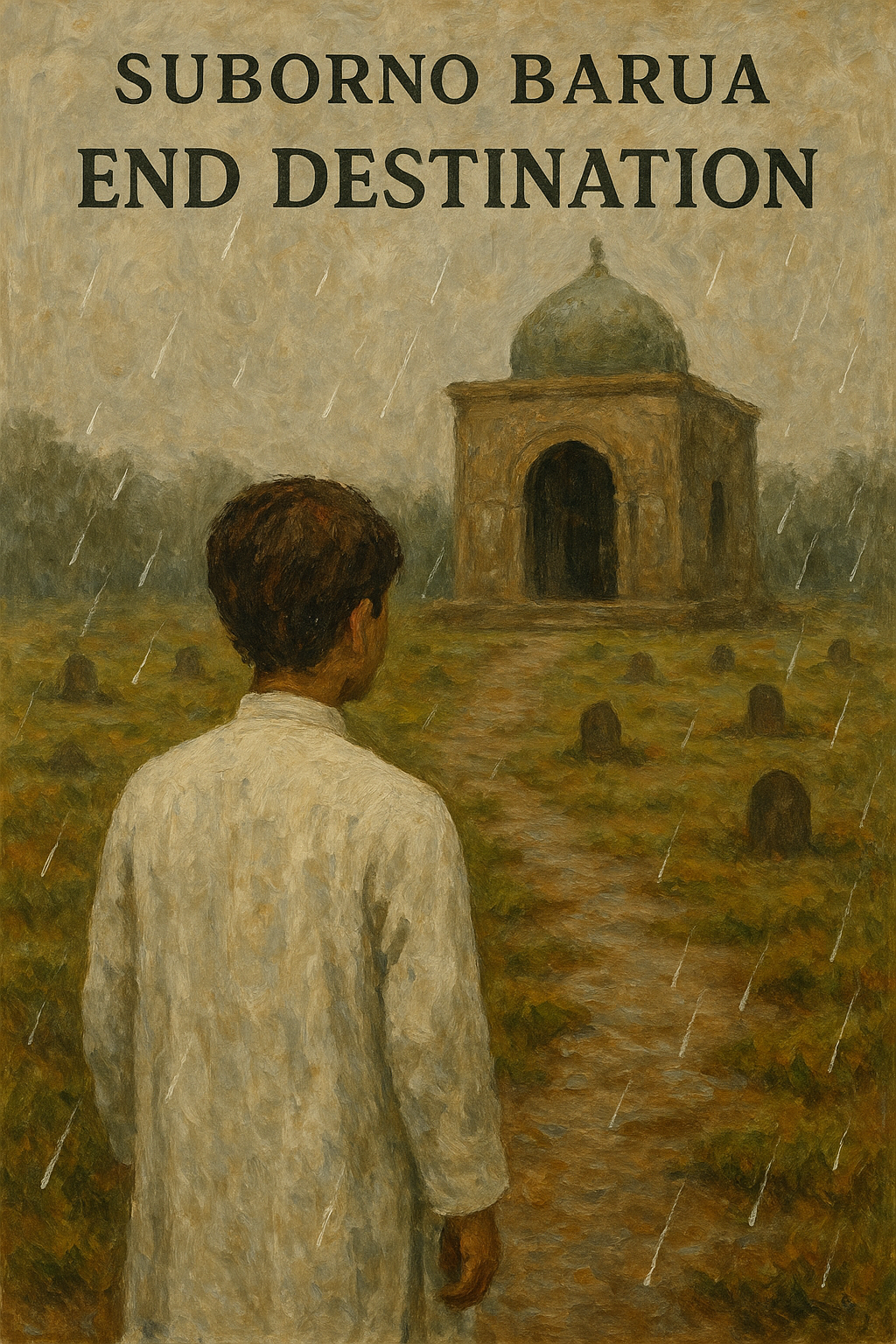

The first thing you notice about the room is the smell. It’s not dirty exactly—just old. Like clothes that haven’t dried properly. The walls are cracked, stained with years of oil and smoke. There is no window. Just one flickering bulb hanging from a wire that looks like it might fall if you breathe too hard. This is where Farzana lives, along with her mother and two younger brothers. They came to Iran two years ago, fleeing the chaos that swallowed their life in Afghanistan. Her father had disappeared during the fall of Kabul. With no money, no future, and no man to protect them, her mother made the only choice left: escape.

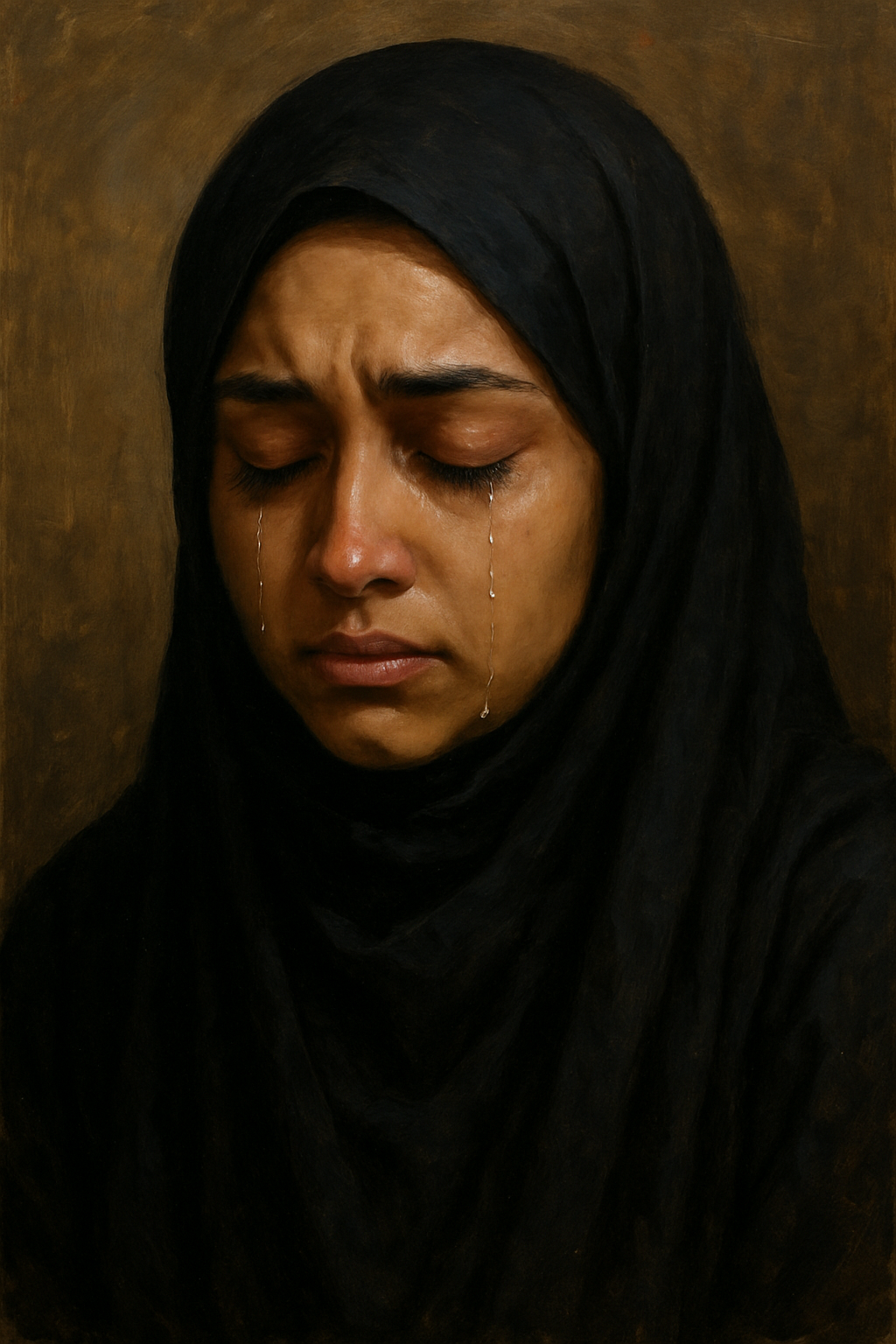

Farzana was seventeen when they crossed the border. She’s nineteen now, and the only one in her family who earns. Every morning before the sun rises, she ties her scarf tightly around her head and walks forty minutes to a garment factory. Her job is simple: sewing hems on dresses that she herself could never afford. She works from sunrise to late afternoon and earns just enough to pay rent and buy a little food. They live off lentils, bread, and sometimes, if they are lucky, eggs.

Her boss calls her “Afghani” instead of her name. The other workers avoid her or push her aside in line. When she speaks, they pretend not to hear. She swallows it. All of it. Because she knows what happens to Afghan migrants who talk back. She has no papers. No ID. No protection. All she has is silence, and the instinct to survive.

She saves half of her bread every day to bring home for her brothers. She wraps it in thread paper from the factory floor. Sometimes, another girl—also Afghan—shares an egg or a piece of fruit. They don’t talk much, just exchange small kindnesses like soldiers in the same trench.

She dreams of having a room with a window. That’s it. Not a big house or money or even citizenship—just a single window. Somewhere she could sit and see the sky. Some nights, when the factory noise still echoes in her ears and her brothers are asleep, she writes in a notebook she hides beneath the mattress. She writes poems—little ones, never finished—about missing her father, about how silence tastes, and about a girl who walks freely down the street without fear. One line she writes again and again: “If I disappear, will anyone write my name?”

One morning in early June, just before starting her shift, a girl at the gate whispered something that made the hair on Farzana’s arms stand up. “They found her,” she said. “That Afghan girl in Varamin.”

Farzana didn’t know the name at first. But soon, the whisper passed from mouth to mouth: Kubra Rezai. A young Afghan woman. Gone missing in April. Found dismembered near the train tracks. No investigation. No justice. Her family was silenced. The media was warned. Her name barely made it past the walls of migrant neighborhoods like theirs.

Farzana didn’t know her, but suddenly, she felt like she did. The fear in her stomach felt too familiar. The silence after the name was spoken reminded her of all the moments she’d felt invisible. All day, her hands couldn’t stop shaking. She kept thinking, “That could have been me. That still could be me.”

That night, Farzana took out her notebook and wrote one last poem. It was messy, unpolished, not really a poem at all—just a stream of pain and quiet rage.

Kubra,

I never met you.

But I carry your name like a prayer in the dark.

They tried to erase you,

But I will not let them.

You were one of us.

And we will not forget.

Then she closed the notebook and looked up at the ceiling, at the old bulb still flickering above her head, and she whispered the only thing that gave her courage: “I’m still here.”

And as long as she is here, she will remember.

And write.

And one day—when the window finally opens—she will shout the names of all the girls who were never given the chance.

For Citation/Reference (APA):

Annabi, A. (2026). When a Women Has No Identity. JMAG, 1(1), https://jmag.jaamir.com/the-room-with-no-window/